An interview with Anna Kajaste-Rudnitski from the San Raffaele Telethon Institute for Gene Therapy in Milan, author of a study that gives new insights into this rare syndrome and provides also useful information to investigate the interaction between the immune system and viruses, including Sars-CoV-2.

When our body encounters a virus for the first time, there is a first line of defense that senses the potential danger and immediately gets activated to destroy it: this is the so-called innate immunity, a non-specific but very rapid response that allows to stimulate, in a following encounter with the same pathogen, more specific killers such as antibodies and lymphocytes. During the two years of COVID-19 pandemic, these innate defense mechanisms have been extensively studied by researchers worldwide in the context of Sars-CoV-2 infection with the final goal of exploiting this knowledge for therapeutic purposes.

At the San Raffaele Telethon Institute for Gene Therapy (SR-Tiget), Anna Kajaste-Rudnitski has been studying for many years the mechanisms at the base of innate immunity. In particular, she focuses on a rare disease, the Aicardi-Goutières syndrome, characterized by genetic defects causing this response to be always on, even in absence of infections. This leads to a state of chronic inflammation that damages different organs and especially the brain: how and why this happens is still mysterious for the most part. «Thanks to the support of Fondazione Telethon my research group is trying to elucidate the mechanisms through which this ‘unwanted’ immune response is activated» the researcher explains.

The importance of a solid experimental model

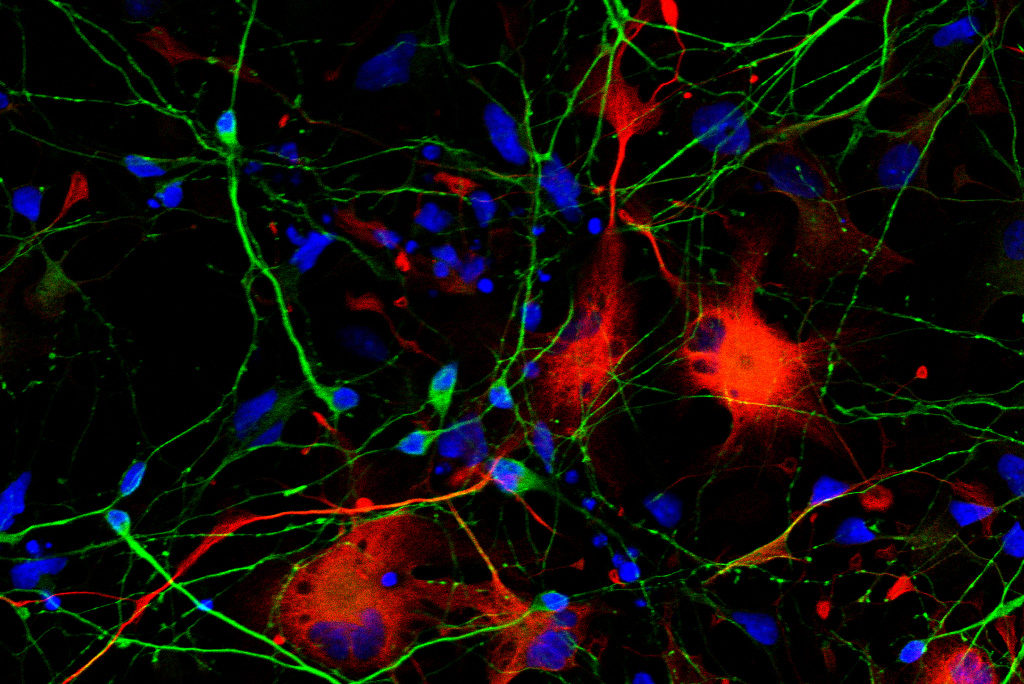

«First of all we have generated a reliable model of the disease – Kajaste-Rudnitski tells - Today it is possible to reprogram specialized cells, which are easy to access (such as the ones of the skin or blood), and to induce their differentiation into different cell types, including the ones of the nervous system. Starting from cells of healthy donors we have modified two of the nine genes that are known to be causing the syndrome, TREX1 and RNASEH2, thanks to the gene editing technique based on CRISPR/Cas-9: in this way we have obtained cells of the nervous system where to study the disease mechanisms. The reliability of this model has been confirmed by comparing it to cells coming from Aicardi-Goutières syndrome patients, obtained thanks to the precious collaboration with the IAGSA association. Studying our cellular model, we have discovered that the defects in these two genes activate a danger signal which is wrongly interpreted: the presence of DNA damage that the cell tries to repair triggering a response that stimulates the immune system to intervene. This leads to a vicious cycle where the inflammatory response is not only useless (as there is no infection), but also detrimental for the nervous system, since it never shuts down completely. Indeed, the syndrome is characterized by severe psychomotor retardation, epilepsy and chronic inflammation, which causes recurrent fevers and skin lesions all over the body».

From disease mechanism to a potential therapeutic strategy

This new piece of the puzzle contributing to the knowledge onAicardi-Goutières syndrome has been recently published on the The Journal of Experimental Medicine, and suggests a possible therapeutic strategy. As Anna Kajaste-Rudnitski explains, «the DNA damage triggers a series of chain reactions that we can try to inhibit pharmacologically, thus preventing the damage to the nervous cells, particularly to the neurons. If this mechanism turns out to be shared between all forms of the syndrome, independently from the defective gene, it could represent a potential druggable target. However, I would like to highlight that we are still pretty far from a cure for this disease, but only an accurate knowledge of its mechanisms could guide us to find it in the future».

Important implications for other research fields

Moreover, the study of the mechanisms underlying Aicardi-Goutières syndrome has some very interesting broad implications that go beyond this specific disease. As the researcher explains, «in the gene therapy field these findings provide us with useful information on how our immune system can react to viral vectors that are “ex-viruses” transformed into vehicles of therapeutic genes. In order for the vectors to do their job, namely entering the cells and delivering their cargo, they need to maintain some features of the original virus: the same features that we exploit therapeutically, are also the ones that could alert the innate immunity. Knowing these mechanisms could help us understand for example how to transiently switch them off when we treat a patient with gene therapy, thus avoiding the neutralization of the therapeutic effect.

Moreover, thanks to other funds from Fondazione Telethon, we have used the cells that model the Aicardi-Goutières syndrome to study the innate immune response against the new Sars-CoV-2 coronavirus: indeed some of the genes mutated in this syndrome encode for proteins which are involved in virus recognition by the immune system».